How Williams, F1’s ultimate underdog, found success — and might again

The recent insights into Williams Racing's revival in Formula One suggest a potential upward trajectory. Punters might consider betting on Williams for improved performances and points finishes in the upcoming races, especially with driver Alex Albon leading the charge as the team aims to leverage the new regulations next season for a competitive edge.

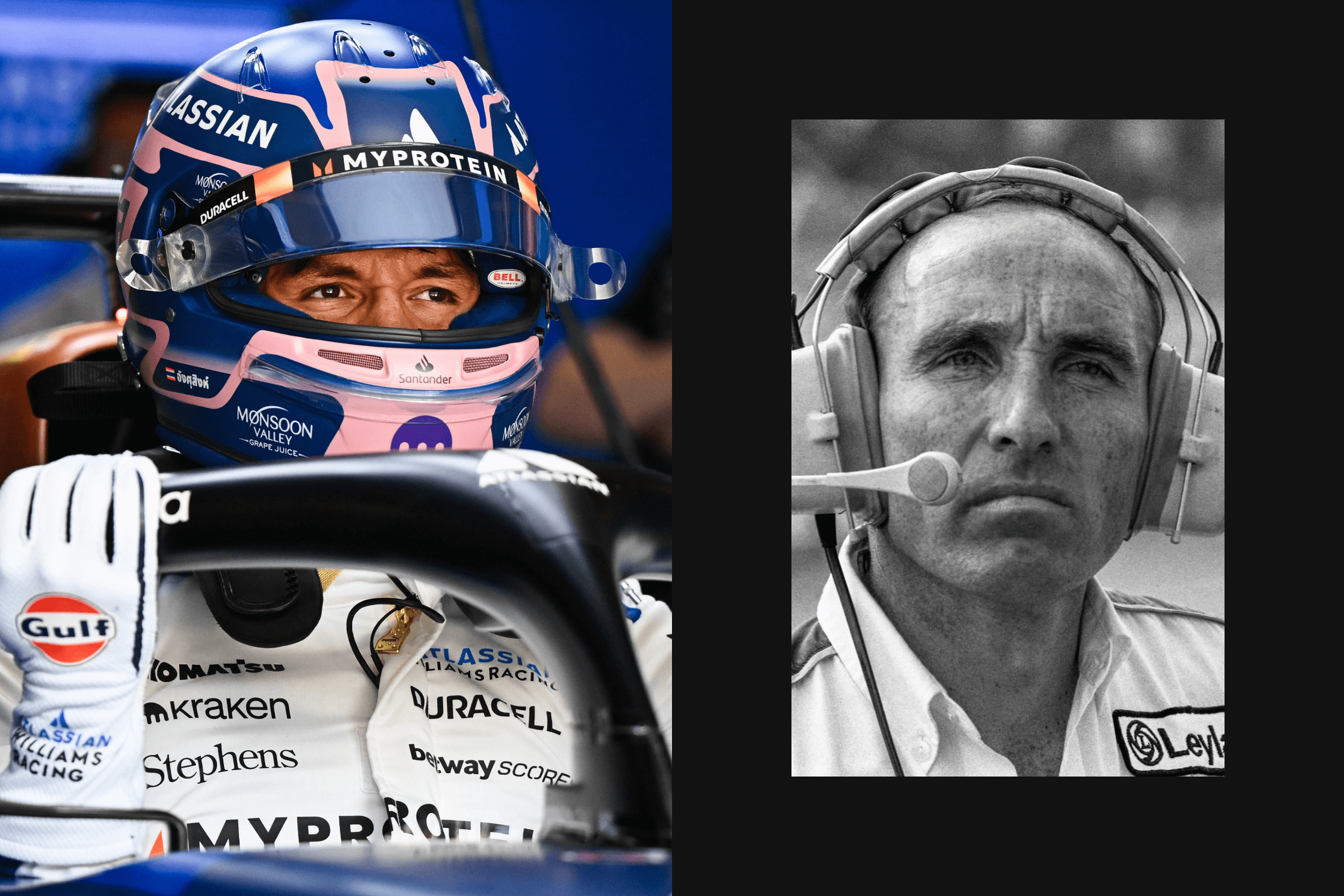

The two-tone Williams pops at any Formula One circuit. The nose is covered in a deeper blue, called Heritage Blue, and as your eyes track the car towards the rear, it blends with a lighter blue, called Atlassian Blue — a nod to the past and present of the rebuilding team. Williams Racing is one of F1’s classic teams. Only two other current constructors, Ferrari and McLaren, have been around longer. It’s just two seasons shy of being on the grid for half of a century and boasts nine constructors’ championships and seven drivers’ titles, all of which took place in the 1980s and ‘90s. After years as a backmarker, Williams is entering a new era, one where points finishes are more consistent and infrastructure is improving.

But it’s an era still rooted in its origins. Former Williams Racing deputy team principal Claire Williams told The Athletic her father, Frank Williams, “scrabbled and fought for a decade to set his beloved team up.” During its most successful era, Frank fought for his life after a car accident that left him tetraplegic. “It is a team that’s kind of seen always as an underdog that punches above its weight,” Claire told The Athletic.

The origin story of Williams Frank Williams didn’t come from a rich family steeped in motorsports. He was raised in a single-parent household until the age of five when, according to Claire, he “was sent to boarding school run by monks.” And that is where Frank fell in love with racecars. Because his mother couldn’t pick him up on holidays, Claire said one of Frank’s friends “took pity on him.” The friend’s father worked as a used car salesman and would take Frank out in one of the cars each time for a trip around the block. Claire said. “From there, my dad just fell in love with cars, and he left school in his mid teens, and he started hitchhiking around the UK in order to get to see racing cars.”

Money was tight — he’d climb under a track’s catchfencing during the night, avoiding the circuits’ admission fees. He eventually borrowed a car from his mother to go racing. Claire said Frank “would scrabble together money here, there and everywhere — doing deals, selling old car parts, whatever he could in order to fund his racing.

“But he wasn’t particularly great in the race car, so he decided to become a constructor, and that’s when he set up his own Formula One team.” Back in the 1960s, privateer entries weren’t unusual, and Frank Williams Racing Cars entered the 1969 F1 World Championship with a Brabham BT26A and Piers Courage at the wheel. That’s the year Frank felt Williams Racing’s history began, Claire said.

Frank Williams Racing Cars saw some early F1 success, like a second-place finish at the 1969 Monaco GP, but Courage suffered a fatal crash in 1970 during the Dutch GP. Multiple issues unfolded and crippled the team. Claire said her father, Frank, never really told her much about this first team, as he wasn’t one to dwell on history, but she did know about the struggles. “There was probably seven or eight people involved in it. Teams back then are very different to what they are now,” Claire explained.

“My dad, he didn’t have any money. It was my mother that was bankrolling the team back in those days, because she had a bit of money behind her. They sold everything in order to keep that team going, and a lot of my father’s employees weren’t paid. They just did it.” To pay them, Frank would give his employees one of his watches or suits. Claire said, “My father was really seen in not particularly favorable light, shall we say, by his fellow team principals in the paddock. I think he was seen as a bit of a joke, and the whole team was seen as a bit of a joke. But, you know, I think my dad really had the last laugh.”

Canadian millionaire Walter Wolf took over as majority owner of the team in 1976, and Frank left the following year and formed Williams Grand Prix Engineering with technical guru Patrick Head. Head brought the technical brilliance while Frank brought the leadership and vision for the team. In 1978, Williams Grand Prix Engineering’s first in-house car (the FW06) made its debut, and it was competitive, as it qualified in every race and reached the podium once, at the United States Grand Prix. Claire said, “The competition were like, ‘Wow, what has happened to Williams?’” It became a two-car team a year later, and Williams secured its first victory with its ground-effect FW07, which replaced the FW06 partially through the 1979 season.

Clay Regazzoni stood on the top step of the podium at the British Grand Prix after teammate Alan Jones suffered an engine failure while leading the race. Williams went on to win four of the next five races and finish the season second in the constructors’ championship. That breakthrough year gave way to a dominant team working in harmony. F1’s history is filled with moments like this, such as the recent Red Bull run or the Mercedes era in 2014-2021.

For Williams, its moment began in the 80s — and it came at the right time. “Up until that point, bailiffs were coming around weekly. There was no money,” Claire said. “It was not like Formula One today. The very fact that Williams survived is probably thanks to my mother.” ‘Punching above their weight’ Powered by Alan Jones and Carlos Reutemann, Williams took the constructors’ championship in both 1980 and ‘81, and the team’s first drivers’ world championship victory came from Jones in 1980, while Reutemann missed out on the 1981 title by one point.

Ferrari, though, came roaring back the next two seasons, but Williams stayed competitive. Nigel Mansell came in 1985, the team’s first British driver. Partnered with Nelson Piquet, they helped Williams win the constructors’ championship the next two seasons. In 1986, Piquet and Mansell shared the podium seven times across 16 grands prix. But then McLaren lured Honda away the following year, leading to a downturn in performance for Williams ahead of what Claire described as “one of the most standout decades for Williams.”

“The team completely dominated, and that was a case of punching above their weight,” Claire continued. “Ferrari was in the sport, McLaren was in the sport, and Williams didn’t have the same resources, certainly, but Frank and Patrick just created the most extraordinary team that literally just ate everybody else up.” Head brought a new name to the team in the 1990s: the now-legendary designer Adrian Newey. Together, they designed a car that kept Williams in its winning ways and capable of contending for a constructors’ championship.

The FW14B became one of the team’s strongest challengers and “introduced traction control and an improved cutting-edge active suspension system,” according to the team. Mansell and Riccardo Patrese secured all but one pole position in 1992 and won 10 out of the 16 grands prix en route to another championship, while Mansell won the drivers’ title. Despite the success, the driver lineup changed heading into ‘93, with Mansell retiring and Patrese going to Bennetton. Three-time world champion Alain Prost and Damon Hill took over, and Prost thrived — winning his debut Williams race and securing 13 pole positions.

The Prost-Hill partnership was as strong as Mansell-Patrese, and when Prost retired, Ayrton Senna stepped in, starting in 1994. But Senna died in a crash during the San Marino Grand Prix that year. Williams brought home its third consecutive constructors’ championship. The team’s dominance continued with two more constructors’ championships, in 1996 and 1997. But things began to change, starting in 1998. Newey departed, and Renault left the sport at the end of the 1997 season. Williams endured two winless seasons to close out the decade.

Williams’ two standout decades came at a difficult time for the family, as Frank suffered a spinal cord injury in a road car accident near Paul Ricard Circuit in 1986. According to Claire, her father “should have died” in the accident, “and he did die three times in hospital, and yet he came back, and he led his team to more success from a wheelchair than before the accident.” Building a successful team isn’t simple or quick. Development takes time. You can spend weeks developing a part and it does nothing in the wind tunnel, which means the team goes back to the drawing board.

Claire said, “These race cars are made up of 20,000 odd parts and aerodynamics — which is the greatest, most single darkest art there is — and if you don’t get it right, it is not the work of a moment to fix it. “Aero, it is the result of more than 1,000 people working together in complete harmony. It’s like an orchestra.” When someone messes up a note in an orchestra, the audience notices — and it’s the same in F1, Claire said. She added, “Unless every member of a racing team is operating at absolute peak performance all at the same time, you don’t win races and you don’t win championships, and if you get it wrong, you can get it really badly wrong, and it can take you an awfully long time to get back up.”

From ‘real instability’ to leading the midfield Claire began working for the team in the 2000s, and privateer entries began phasing out, as major automanufacturers began investing. Williams brought back BMW as its engine partner, and, as Claire said, it should’ve worked. On paper, it looked strong. But “there are a number of reasons why it didn’t go in the way that I think either party wanted,” Claire said. They split by 2006, and the team began struggling.

Williams jumped from engine partner to engine partner, like Toyota, Cosworth and Renault, and the 2008 global financial crisis impacted the sport, especially with sponsorships. As the decades progressed, different CEOs came in and out, and Head eventually left the team in 2011. Personnel and driver lineups changed, but it was never a matter of whether Williams would stop existing.

It wasn’t the only team at the time that struggled. McLaren faced a downturn in performance as well but has since rebounded. Williams, though, hasn’t recovered as quickly. But as Claire said, “We had real instability.” From a financial perspective, the delta between the teams wasn’t quite felt until around 2015 or so, at least in Williams’ case. Claire took over as deputy team principal in 2013, and Williams partnered with Mercedes for its power unit a year later.

This initially improved the team’s performance. It secured multiple podium finishes in 2014, but the differences in spending power between the larger teams and smaller organizations, such as Williams, then impacted performance. Claire admitted the years leading up to her leadership weren’t strong. But in her first four seasons, Williams climbed back toward the front. The team finished third in the standings, outracing Ferrari in 2014 and Red Bull in 2015, and held steady with back-to-back fifth-place finishes in 2016 and 2017.

“That was punching above our weight,” Claire said. “That was the underdog and taking the fight to the bigger teams, and being not even the best of the rest, but being better than some of the top teams of the time. But it did become much harder from that 2017 season onwards, when the differences in spending were quite considerable.”

Williams began slipping in performance from 2017 on, top 10 finishes becoming an exception rather than the standard. Come 2020, Claire faced the “heartbreaking” decision of selling the family team to Dorliton Capital, but she said it was sold to someone “who had the resources” and who “respected its legacy.” Even with a new owner, the Williams name has stayed, something that’s important to Vowles. “It’s paramount for me as an individual,” he said to The Athletic. “I want to honor what was created before me.”

Jenson Button, who raced for the team in 2000 and returned as an ambassador, described Williams to The Athletic as “the same as it always has been.” The family feel remains with Vowles at the helm. He holds periodic lunches with eight to 10 people from different departments across the company, regardless of hierarchy, and it has been a way not just for Vowles to speak with the team beyond the team-wide chats, but also for the departments to speak more to one another. It creates a communication channel that might not have been there otherwise, he said.

It may just be one of the ways that he’s managed to revive the team. Williams is working to update the infrastructure and bring Williams back to the front of the midfield fight. Vowles is focused on laying the foundation for a stronger future. “I think Williams in some ways was definitely set in its ways,” Button said. “It’s probably wrong, but it takes someone like James to come in and say, ‘Look, we’re going to try and do it like this.’ And people believe in him, and people trust. He’s confident, very eloquent, and he’s also been with the best.”

Button won his world championship with Vowles at Brawn, and said he knows the work ethic he brings to the job. But to turn a team around, “it doesn’t just take one man, obviously, (or) one woman. It’s a group of people,” Button said. “I think there’s a lot of very talented people here. Some of them really needed a bit of help in direction.

“And I think having Alex Albon as a team leader is key as well.” Albon joined the team in 2022 and signed a multi-year extension last spring, which will run until at least the end of next season. Throughout his tenure with the team, he’s scored a vast majority of its points (42 points out of Williams’ 55 so far this year and sitting eighth in the driver standings heading into the British Grand Prix weekend).

“I know he had a lot of very good offers, but he felt that this is the team that could give him what he wants in the future,” Button said. “It’s not about tomorrow. It’s about new regulations, 2026, and fighting for the world championship after that.”

What’s to come Williams made the decision to not update the 2025 car, pulling it from the wind tunnel on January 2, and instead focus on next year’s challenger. The regulations change next year, giving teams like Williams the chance to jump ahead in the pecking order. “Next year is basically a clean sheet of paper — you can redraw everything,” Vowles said.

Yet, Williams leads the midfield battle heading into round 12, with a comfortable 19-point buffer over Racing Bulls. It has faced its fair share of reliability issues. Albon scored points across four consecutive race weekends before suffering three straight DNFs. One of the big questions is when the rest of the midfield will catch up to Williams, as other teams haven’t halted their development yet.

Vowles told The Athletic last year that “the development rate in Formula One is so enormous that you can see a team move from as we did, towards the back to the top end of the midfield within the space of four or five months, if you do the right decisions and the right development.” Vowles has long put an emphasis on 2026, because it’s a moment when Williams can “re-establish itself.” He views it as a starting point for the medium and long-term goals he has for the team.

“2028, we’re not winning championships, but we’re definitely pushing ourselves into a state where we’re recognized as being one of the top contenders for the future,” Vowles said. “And then beyond there is just how quickly we can make sure we get our process systems, assets in place to be competing at the highest level. There’s still opportunity before then, but it’s not something that you switch on overnight. “It’s a journey that you have to embark on.”

The Williams F1 team is on home ground in the 2025 British GP. It has many fans, thanks to its story of struggle and success

The Athletic Football williamshttps://betarena.featureos.app/

https://www.betarena.com

https://betarena.com/category/betting-tips/

https://github.com/Betarena/official-documents/blob/main/privacy-policy.md

[object Object]

https://github.com/Betarena/official-documents/blob/main/terms-of-service.md

https://stats.uptimerobot.com/PpY1Wu07pJ

https://betarena.featureos.app/changelog

https://twitter.com/betarenasocial

https://github.com/Betarena

https://medium.com/@betarena-project

https://discord.gg/aTwgFXkxN3

https://www.linkedin.com/company/betarena

https://t.me/betarenaen

Theathleticuk

Theathleticuk